As a server engineer in EA’s All Play label I have worked on building a number of REST services to support mobile and social games. These include The Simpsons Tapped Out, WSOP Poker, Pogo Facebook and Pogo iPhone. One common consideration that came up in all of these projects is the choice of a transport protocol. The choice of protocol is specially important for cross-platform games as they use multiple languages (Objective C, Java and As3 in our case), may use spotty mobile networks, are supported for years and have un-controlled client update cycles. This means we need a protocol which is well supported, concise and backwards compatible. In my various projects I have used several protocols including XML, JSON, Thrift and Protobuf. Protobuf has become a popular choice among server engineers for its speedy serialization and compact output. While I think Protobuf is very useful protocol in certain situations I would like to argue that REST services are not among those situations. Specially if they have to be developed rapidly, need to be maintainable and easy to change. Most game servers are built on tight schedules, have to be live for years with little or no down time and have constant feature updates.

The Case for Protobuf

Serialization Size

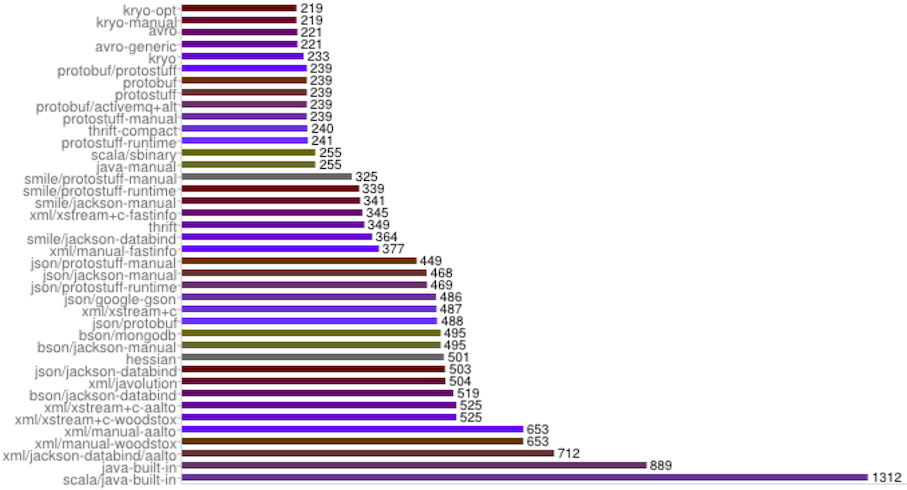

One of the primary reasons people decide to use Protobuf is for serialization size. Benchmarking done by folks at the thrift-Protobuf-compare project shows that Protobuf tends to very concise. For the Test Data we see that Protobuf serializes to 239 bytes in comparison to raw java, 889 bytes. This is a valid concern on mobile networks where bandwidth can be expensive and connections lossy, making large objects a liability.

Serialization Time

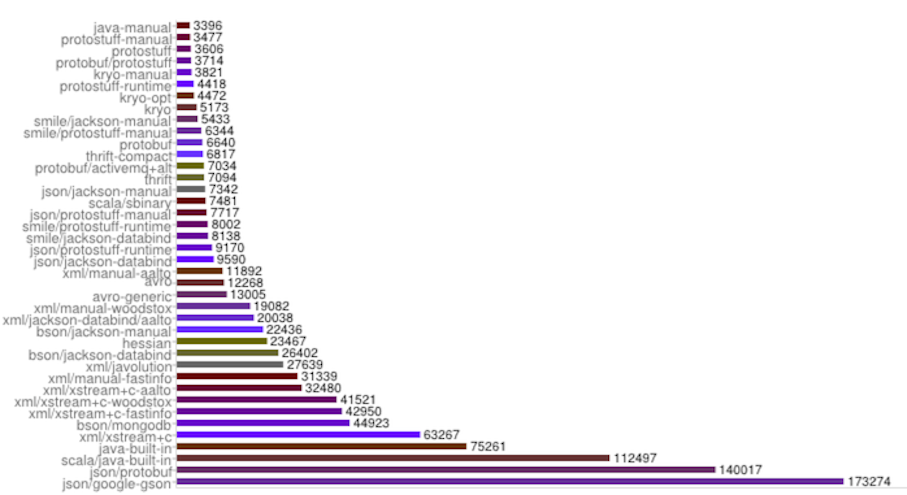

In addition to being concise, Protobuf is fast, again curtesy of our friends at thrift-Protobuf-compare we have benchmarks for this too. Protobuf clocks in at 6640ns to create an object, serialize it and deserialize it again. Even the fastest XML implementations take twice as much time and Java built in serialization takes 10 times as much as time.

Code Generation

The third most commonly highlighted feature of Protobuf is its ability to generate code bindings in various languages. This allows for strong typing and compile time error checking. We can use the same source Protobuf files to generate code for both server and client(s). This means the object model on the client and server can be kept consistent. If someone on the server team changes the definition of a Protobuf message the client build should also break (if Protobuf compilation is integrated into the build).

So what’s the problem?

Not Human Readable

The first problem I always have with Protobuf based projects is how to do dev-testing. When you first write a new servlet, before you have any API tests or even have completed much code you will want to send Http requests to a server instance in your dev environment and test your code. With any human readable protocol I can hand craft a request and test all of the use-cases using a simple REST client such as Poster. With a binary protocol such as Protobuf we need a tool to generate the request we want to test with. With Protobuf this loop may be even longer as may need to update the source proto file, generate code, update tool, update request parameters, generate binary data, send to server. This may seem like just an irritant but the development process slows down considerably when a task this fundamental has so many steps. In addition, this leads to developers who are not going to test all the edge cases.

No Inheritance

Another major problem with Protobuf is that there is no way to make inheritance hierarchies and interfaces. In most servers I have written for games there is a great deal of overlap in the objects that are sent from client-to server. In the poker server we have a user object with minor changes for Facebook users vs Origin users. We have a purchase object with minor differences for iOS purchase, Android Purchase and Kindle purchases. Protobuf forces us to use either one object with lots of optional fields or repeat the common fields in each objects. Both these options are unsavoury, the former tends to be error prone as there are fields that should be ignored but may or may not be depending on bugs. Having null fields also erases some of the benefit of having a compressed protocol. The latter option leads more code as we have to repeat all verification and validation code for various classes with identical fields.

No Polymorphism

A related problem is the lack of polymorphism or views on top of the Protobuf objects. In some of our projects we have used Jackson views to good effect. We use the same object to accept input from clients, add server-side meta data and then serialize the data for storage into the database. We use views to control what gets serialized to the database, what gets written over the network for clients to see and what is only stored in memory as the object makes is way around the server code. With Protobuf any fields in the object are accessible to all consumers of that object. In order to implement views we either have to make multiple definitions of similar objects for the various uses or write code to null out fields before serialization. This does not lead to the most elegant code and makes the project more difficult to manage.

No Self-descriptive objects

One of my pet peeves with Protobuf and similar protocols is that they use IDLs to define the structure of objects but do not encode it into the serialized output. Therefore the IDL generated code needs to be pushed into the builds of all the various projects that send and receive Protobuf objects. Furthermore, even with all the generated code in place the receiver still needs to know which object it is receiving a-priori otherwise it will not be able to apply the correct IDL defined structure. One common solution is to have a large “Message” object which contains optional fields for all possible data transfer objects. All but one of the fields will be null. Another solution is to use HTTP headers or REST URIs to define which type is being expected. It would be much cleaner if objects were self-describing.

So what do we use instead?

The prior section naturally begs the question of what should be used instead and in my opinion the answer is JSON. For our Simpsons and Poker Servers we use the Jackson library on the server side to map client requests directly to POJOs and server responses back to JSON. Using Polymorphic Serialization we are able to create entire hierarchies of client requests which can be read from the wire without any prior knowledge of which object we were receiving. Using Jackson Views we are able to have fields in the same object which are client visible but not stored in database, stored in the database but not client visible and in memory only. Lastly, as the incoming JSON is mapped to hand-crafted classes we can write code in them. This proved invaluable in writing concise and elegant code. We were able to reduce our servlets to 3 lines of code shown below. The rest is taken care of using polymorphism, each request object knows how to process the incoming data and generates a sub-type of the ServerResponse object.

1

2

3

ClientRequest request = jackson.readValue(...);

ServerResponse response = request.doProcessing();

String response = jackson.writeValueAsString(response);

As an example I am see the layout of our Purchase Processing code. This small code snippets handles our entire purchase flow in conjunction with the 3 lines above.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

public class ClientRequest {

String sessionToken;

@Override

public void doProcessing() {

//Verify session

}

}

public class PurchaseRequest extends ClientRequest {

String itemId;

String userId;

@Override

public void doProcessing() {

super.doProcessing();

}

public void grantItem() {

//Grant item to user

}

}

public class AndroidPurchase extends PurchaseRequest {

AndroidReciept reciept;

@Override

public void doProcessing() {

super.doProcessing();

//verify Android Reciept

super.grantItem();

}

}

public class IOSPurchase extends PurchaseRequest {

IOSReciept reciept;

@Override

public void doProcessing() {

super.doProcessing();

//verify iOS Reciept

super.grantItem();

}

}

Protobuf code for a similar project would have been some similar to the snippet shown below. The difference in maintainability and clarity is stark even in such a small example.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

ClientRequest request = ClientRequest.parseFrom(...);

Session session = request.getSession();

//verify Session

if(request.getType == PURCHASE_REQUEST_TYPE) {

PurchaseRequest purchaseRequest = request.getPurchaseRequest();

if(purchaseRequest.getType() == ANDROID_REQUEST_TYPE) {

AndroidPurchase androidPurchase = purchaseRequest.getAndroidPurchase();

AndoridReciept androidReciept = androidPurchase.getAndroidReciept()

//verify android reciept

} else if (purchaseRequest.getType() == IOS_REQUEST_TYPE) {

IOSPurchase iosPurchase = purchaseRequest.getAndroidRequest();

IOSReciept iosreciept = iosPurchase.getIOSReciept()

//verify android reciept

} else {

throw Exception(...);

}

} else if (...) {

} ...

Using our approach we had no repeated code and were able to write very stable server despite that fact that during this project our team grew from 1 person (me) to 5. Each was able to quickly ramp up and contribute to the project as there was a clear demarcation of object responsibility and all code relating to one feature was in one place. Furthermore dev testing was greatly improved because we could quickly hand craft client requests and see how the server behaved. Once we had our code stable the same hand-crafted JSON could be used as input to unit and integration tests. If there was a bug reported against the server, the client team could post the exact JSON which caused the problem and also quickly verify it was resolved without using any code.

We have seen that JSON clearly is easier to work with than Protobuf and also leads to cleaner and more concise code but there are still concerns about the size of serialized objects and the serialization time. If you look at the times above you will note JSON/Jackson serializes in 7342ns and serializes to a size of 468 bytes. Although JSON is slower and larger than Protobuf the differences are not huge and on modern devices and networks the there should be little or no noticeable impact. In poker we sent several dozen profile items to the client about each user and still our objects were rarely larger than a kilobyte. Even over lossy networks the transfer time was a negligible percentage of the round-trip response time.

If however your use case is sensitive to such small serialization times and sizes than you can use the Jackson Smile protocol. Smile is an optimized binary implementation of JSON and If you look at the serialization time for smile/jackson you will see that it is actually faster than Protobuf by about 1200ns. Serialized smile objects are still a 100bytes larger than the equivalent Protobuf objects because smile is still self describing. One of the benefits of using smile is that the Jackson parser is capable of parsing both smile and JSON without and configuration changes. This means that the same code can be used with JSON and Smile requests. Hence we can use hand-crafted JSON for dev testing and without code changes we already support Smile. In fact no code on the server is aware of which of the two protocols is being used for the input data. Note, however that smile is not well supported in languages other than Java. This is a big drawback of smile right now but support for smile in other languages is slowly being built out by the open source community.

Conclusion

We have seen how choosing the right transport protocol can make a huge difference in the readability, elegance and architecture of Rest server code. Protobuf and similar binary protocols with predefined classes in IDLs are a bad fit for the architecture of REST servers. The barriers on inheritance, polymorphism and out of band type information makes it more difficult to write elegant and and simple REST server code. Coupled with non-human readable requests such protocols make code much more difficult to test in the early stages of development. With JSON we have a well supported format that is easy to use, extensible, flexible and well supported in most languages. If the serialized object size is an issue we have access to the smile protocol which generates small objects quickly. Although smile is not supported in a wide array of languages it’s protocol is publicly available and support of other languages is and will be built out by open source projects. In the mean time even raw JSON provides near protocol buffer levels of performance for all common use-cases and therefore should be the default choice for a serialization layer.